Projects are about Time, Products about Value

Project management is often wrongly confused with product management. To be fair, it can be a delicate distinction, and the fact that they both start with p doesn’t help. (Not to mention program management!)

The way I’ve been thinking about the difference recently can be captured by the following, where \(J\) is a measure of project success and \(D\) a measure of product success:

\[\begin{align*} J = \frac{\# tasks}{time} \\ \\ D = \frac{value}{\# tasks} \end{align*}\]Project success \(\propto\) 1 / Time

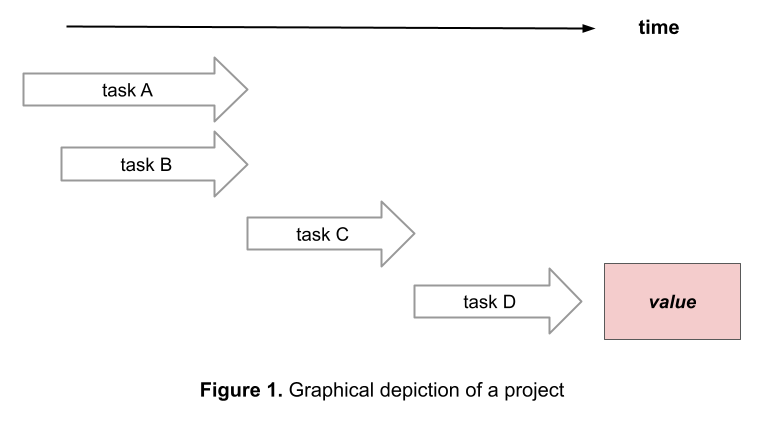

A project can be defined simply as a set of tasks completed by a deadline, or according to a schedule. Usually a project also is something that’s been done before, so there’s already a sense of tasks required and how long they’ll take.

Think of projects like constructing a new home, a very common project where tasks have to be completed in a certain sequence–first the foundation, then the structure, then plumbing, electrical, walls, etc–and there’s a target deadline.

In other words, project management is all about managing the execution a set of pre-defined tasks and, in particular, managing how fast you execute those tasks. The more ahead of schedule a project is, the better. So project success (\(J\)) is proportional to \(\frac{1}{time}\).

Now, projects often hit delays, where new tasks have to be done to address unforeseen circumstances or correct errors. Or “scope creep” adds more work to the original plan. Or sometimes teams even realize some tasks can be skipped or are “out of scope”.

The difference between tasks and time though is that there’s usually a high degree of certainty about how many tasks there are (or how many more/ less you need to add/ substract from the project plan). Whereas there’s always a high degree of uncertainty about how much time any given task will take, and importantly the distribution of completion time is “long-tailed” (i.e. could take much, much longer than expected), especially if they are tasks not expected at the outset. So with every task added, the higher the uncertainty around how long a project will take, and the longer the tail of possible completion times.

So, more completely, projects are mainly about controlling execution speed, but also about making sure to keep the number of tasks constant so to reduce uncertainy around completion time.

Hence \(J = \frac{\# tasks}{time}\).

Product success \(\propto\) Value

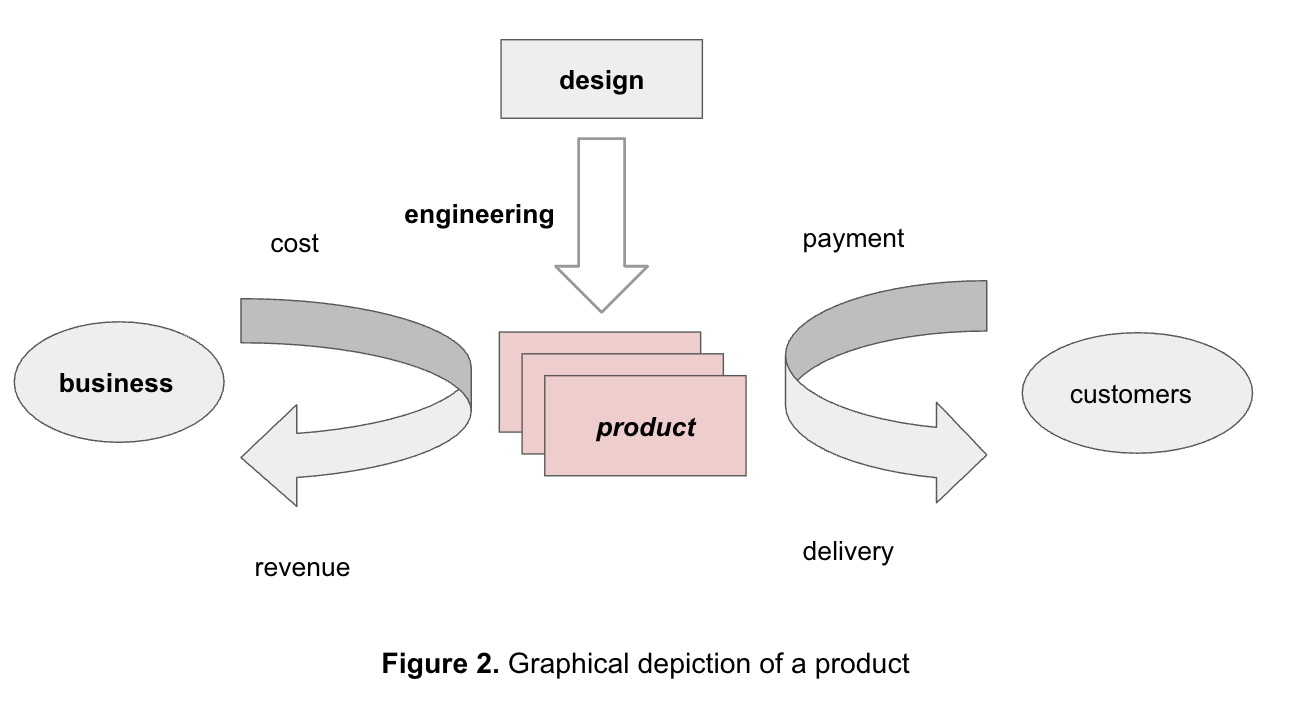

In contrast, products are goods or services that provide value to customers in a predictable, consistent way over multiple deliveries. The purpose of products is also to support the economics of a business over time.

Continuing with the new home construction analogy: a product is not any individual delivered home but the consistent value of all delivered homes. So the components of the product are not deliveries but instead (a) blueprints of the home (design), (b) the construction process (engineering) and (c) the economics of materials, labor and pricing (business). Collectively that’s “the product”.

Those 3 types of product components can then be mapped one-to-one to the management of products, which is the process of: (a) producing designs that create new types of value for customers (design), (b) developing processes that construct goods or services from those designs on a repeatable, consistent basis (engineering) and (c) ensuring those goods or services have attractive economics (business).

However, another noteable difference between products and projects is that products persist and must be improved over long periods of time. They don’t have deadlines. Instead, they are about providing the most value to customers over as long as a time as possible, since the purpose of business is to survive and thrive (i.e. be high value) for as long as possible.

So the higher the value for customers and businesses, the better the product. Product success (\(D\)) then is more proportional to \(value\) than to \(time\).

This also implies the most critical question in product development: what tasks must be completed to develop designs, engineering practices and economics that result in the highest value to customers? And generally, the fewer the tasks the better, since means lower cost for the business (better economics) and faster delivery of value (better for customers). So product success is inversely proportional to \(\# tasks\).

Hence \(D = \frac{value}{\# tasks}\).

Shape of Project v Product Management

So hopefully I’ve convinced you by now that success for projects vs products is very different at a fundamental level.

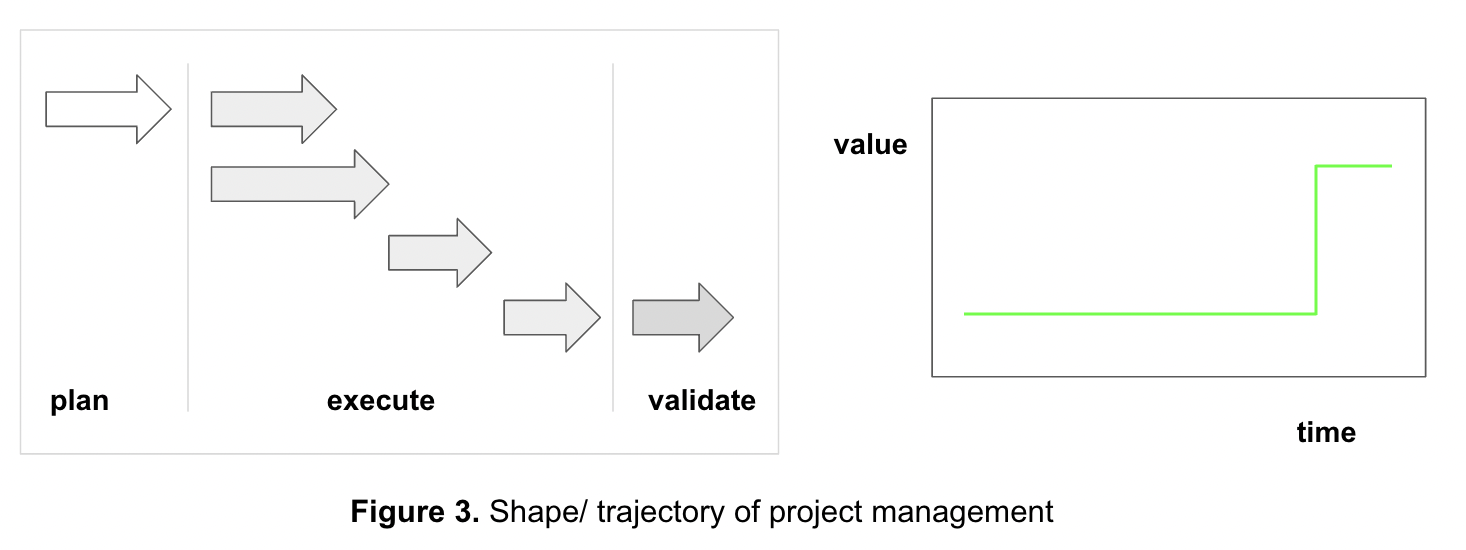

This implies that approaches to project and product management should vary just as differently. To re-iterate, projects are one-off deliveries on a deadline, products are packages of value deliveried and improved consistently over time.

As a result, the principles of project management involve things like schedules, operations, information flow and urgency.

Project processes are linear, like a tree, with value being delivered at the end. Think: Gantt charts.

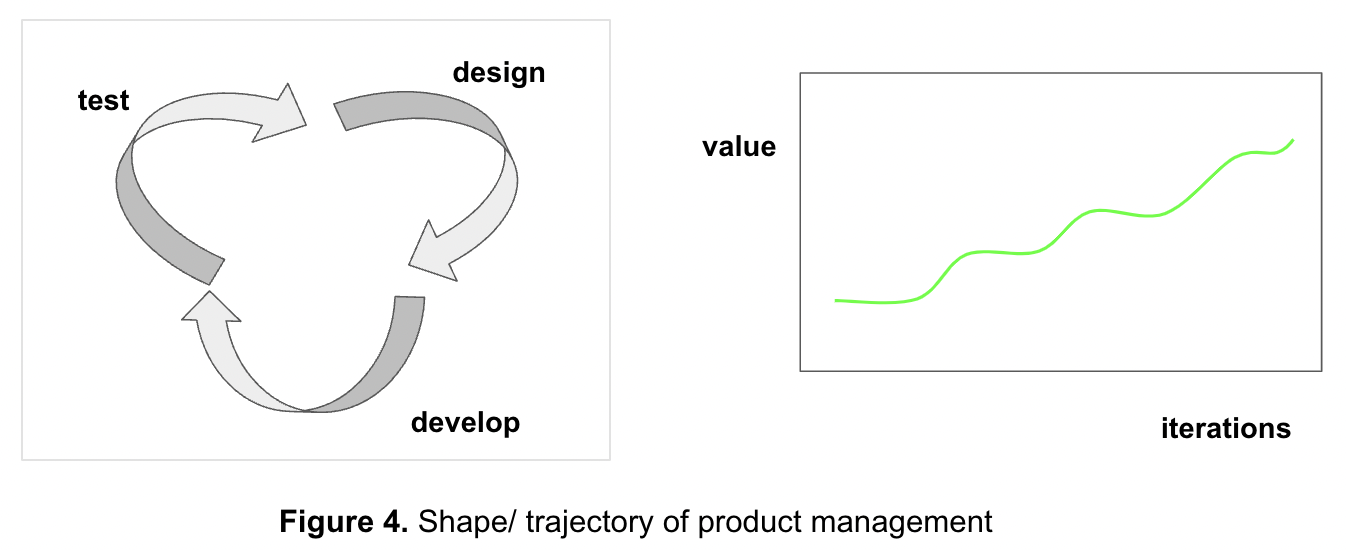

The principles of product management, on the other hand, involve things like experimentation, iteration, feedback loops and importance over urgency.

Product processes are cyclic, iterative, high leverage and focused on constant improvement, with increasing levels of value being achieved at each iteration. Think: iterative cycles.

Project or Product?

So next time there’s some confusion around whether something is a project or a product, ask yourself: is the primary concern time or value?

If time is the primary objective, especially if the set of tasks to be executed is predefined, you should approach it linearly and treat it like a project.

If the primary concern is value, think about cyclic iteration working towards getting to consistent, ideally permenant, value delivery and treat it like a product.

Side Note: Product Development and Evolution

Another important aspect about products: there are a lot of similarities between the process of product development and evolution. The space and dynamics of valuable products and businesses–what we call markets–closely resemble the competition and dynamics of biological ecosystems.

In existing markets/ ecosystems, highly successful products can be “fixed” in the population (i.e. monopolies) because their “traits” have become perfectly suited to their environment, having evolving over many generations. To break into the market/ ecosystem, a new product has to differentiate and exhibit innovative traits to beat out the dominant products. Similarly, to find or develop an entirely new market means searching the space of available or underutilized resources (demand) that can be traded for value (supply) to form a functioning ecosystem/ market.

In either case, you have to have an iterative/ continuous learning/ growth mindset. It’s inherently an evolutionary process to search ecosystems for a valuable niche that can (a) serve as foothold to growing market share in an existing market, or (b) create a new market entirely.

Importantly, either of these could very well be impossible for the type of product/ business being developed, just like a new organism could be ill-suited for the environment it’s being introduced into, or the environment may generally be resource-constrained.

This is depicted nicely in the following figures from the book The Right It, where the left shows an environment with no viable “success” space and the right shows the product search successfully finding a valuable niche.